The Merlin Park Ambush and the Killing of Volunteers Joe Howley & Joseph Athy, Oranmore & Maree, 1920

Revolution in County Galway, 1918-23

Dr Conor McNamara, Historian-in-Residence, 2022

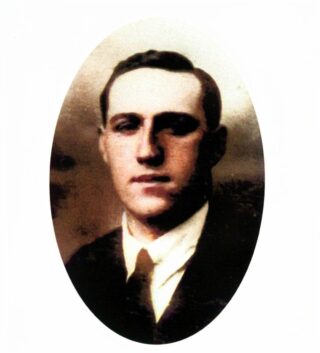

Volunteer Joseph Howley, Oranmore, was a senior officer in the Irish Volunteers and commanding officer Galway No 1 Brigade. He was shot dead by crown forces while he was alighting from the Galway–Dublin train at Broadstone Railway Station in Dublin on 5 December 1920 and died in King George V Hospital several hours later. Howley had served with the Volunteers since the 1916 Rising and the notorious RIC agent, Donal Igoe, who ran a network of undercover police, was widely believed to be responsible for his death. Howley was unmarried and worked in a mill; a statue of his likeness now stands in the village of Oranmore. Howley was central to the actions of the Galway No 1. Brigade throughout the period and the Volunteers in East Galway since their foundation, and his death was a major blow to the organisation in the Oranmore and Maree district.

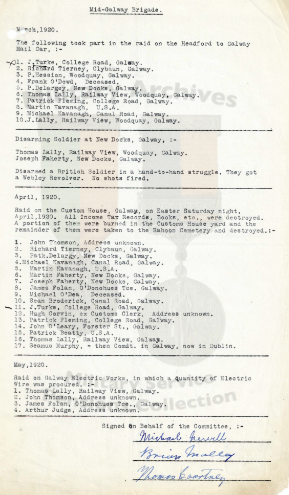

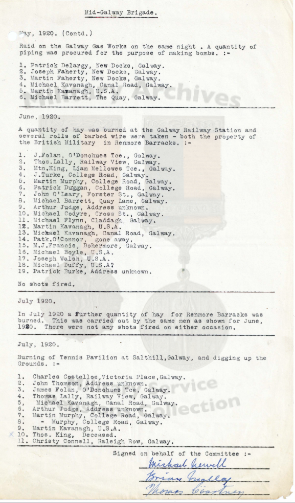

One of the most significant events in the Oranmore district during the independence struggle occurred on 21 August 1920 when the Galway No 1 Brigade attacked an RIC patrol near Merlin Park, killing one policeman, constable Martin Foley, a native of the Castlerea district in County Roscommon.

Volunteer Thomas ‘Sweeney’ Newell of Castlegar left a detailed accounts of events in the Oranmore and Castlegar district with the Bureau of Military History:

During the month of August, 1920, we got reports that five or six RIC men were in the habit of cycling from Oranmore to Galway on Saturday mornings. One Friday night that month a meeting, composed mostly of officers, was held at the forge, Brierhill. I was present and amongst others present were, Brian Molloy, my brother Mick, Thomas (Baby) Duggan and Bernard Fallon. The meeting discussed the possibility of attacking the patrol. It was decided to attack them next morning, Saturday. Brian Molloy was the senior officer present.

We mobilised at Merlin Park wood on the Oranmore–Galway road at 10 am the following morning, Saturday. There were about fourteen or fifteen [men] present. I was armed with a .45 revolver and had five rounds of ammunition for it. Four others had rifles and the remainder had shotguns. About twelve of the party were placed along the wall of Merlin Park at intervals of four or five yards apart, and two on the railway bridge about three hundred yards on the Oranmore side of our position. We were instructed not to fire until after the RIC had been called on to surrender, and they had refused to do so.

At about 12 o’clock noon I saw two RIC men on bikes coming under the bridge, and three others at intervals behind them. Before the leading RIC man reached the ambush position, the men on the bridge, contrary to orders, opened fire on them. We then opened fire. One of the leading RIC men fell. We discovered afterwards that he was shot dead. The other four crawled behind a gateway on the opposite side of the road; the remaining three escaped across country.

When the firing ceased, I went on the road with three others and collected one .45 revolver and five bicycles. I kept the revolver. We dispersed, going home in twos and threes. Later the five bicycles were sent to G.H.Q. in Dublin to be exchanged for rifles. I think that we got five rifles for them. Baby Duggan and Paddy Mullins were on the bridge. Among those in the main ambush position were my brothers, Willie and Michael Newell, Bernard Fallon, Joe Donnellan, Paddy King and Ned Broderick.

Following the shooting at Merlin Park, police ran amuck in the village – a public house and adjoining premises were burned, forcing many residents to flee to the surrounding countryside. The Freeman’s Journal noted:

Following the shooting of a policeman, the police at Oranmore village ran amuck at midnight on Saturday, and burned to the ground the public house of Mrs Keane and the private house which adjoins, whilst shots were fired into the house of Mr Martin Costello, publican. His house was looted and the furniture smashed to atoms. Shots were also fired into the house of Thomas Lee, a private resident, and a cat in a room upstairs was found dead with a bullet wound in its body.

Many of the residents fled to the mountains in terror, and pandemonium reigned until 7 o’clock yesterday morning, when the constabulary, about 20 of whom are stationed in the village, returned to the barracks. Fearing reprisals after the shooting, Reverend Father Casey, Catholic Curate, in the absence of Fr Griffin, the parish priest, on holiday, went to the police barracks and spoke to the men advising them to remain calm. (Freeman’s Journal, 23 August 1920)

The first killing by crown forces in response to the ambush occurred less than a month later. Volunteer Joseph Athy, Irish Volunteers, Ahapouleen, Oranmore, fought in the Maree Company during the War of Independence and was shot dead by crown forces while returning home from work on 17 September 1920. Over one hundred rounds were fired at the cart on which he and his workmates were traveling and another man was seriously wounded.

Athy had joined the Volunteers in 1916 and participated in the republican attack at Merlin Park, the previous month. He was 20 years of age and unmarried and worked with his horse and cart; he died in St Bride’s Home, Galway and was described in the Freeman’s Journal as “an inoffensive young man”. Athy’s workmate, Patrick Burke, was also seriously wounded in the attack and recalled: “one of the boys saw the head and shoulders of a man in uniform beside one of the bushes. Another saw men with rifles going across the fields afterwards.” (Freeman’s Journal, 18 September 1921, p. 5) Athy was most likely killed by members of D Company of the Auxiliaries and elements of the local RIC seeking revenge for the Merlin Park attack.

Joseph Howley, the leading Volunteer officer in the district, was eventually tracked down as well and killed on 9 December when he was shot dead at Broadstone Railway Station in Dublin as he alighted from the Galway train. It was widely believed that Howley – who was not actually involved in the Merlin Park ambush – was killed by Eugene Igoe, a head constable in the RIC, or members of the so-called ‘Igoe Gang’, a network of undercover police whose role was to arrest and/or assassinate effective IRA commanders from rural districts when they visited Dublin. Igoe was a Catholic from a small farm in County Mayo and he was selected for his role as he had personal experience of the Volunteer commanders, particularly in Galway; he was stationed at Killeen RIC hut in Castlegar for several years. Igoe’s gang was composed of rural police specifically selected due to their ability to recognise IRA commanders from their own districts when they visited the capital. William Stapleton, a member of Michael Collins’ intelligence network, known as ‘the squad’, left the following account of Igoe with the Bureau of Military History:

Sergeant Igoe was a policeman selected from some part of Galway to organise a particular Squad of RIC men for the purposes of spotting, interrogation, raids, arrests etc. in Dublin. Apparently, the idea was that the Castle people concluded that a large number of the Volunteers operating in Dublin came from the various parts of the country. The Igoe Squad was built up of representatives of various counties whom it was expected would be better able to recognise the active Volunteers in Dublin and in particular our squad. At this time the activities of the Squad and their reputation had become very great in the city and while Igoe’s Murder Gang, as it came to be called, was probably organised for general duty, I believe that they were specifically developed to combat Squad activities. At any rate we members of the Squad took that point of view and as the Igoe Gang developed we began to feel that our movements were becoming somewhat restricted in that, apart from the ordinary military patrols, policemen, auxiliaries, Black and Tans, staff duties, etc. we had to be continually on the watch for a number of well-dressed men, approximately fifteen, I think, who moved in and out and round the city as would persons on vacation.

Very briefly, the modus operandi of the Igoe Murder Gang was to stroll along the streets, drop into shops, pubs, and restaurants, theatres, attend on the fringes of football matches etc. always on the lookout for country members of the Volunteers and on one being recognised, the well-dressed members of the Murder Gang would quietly move around the individual, or individuals, and smilingly chat and talking quietly, force him into a secluded spot and there, while still chatting and smiling, would interrogate him. Rarely, if ever, did they produce guns. Somewhere within 100 yards or so of the Igoe Gang there was invariably an Army Motor Van and when the Gang decided to arrest an individual a whistle was blown, or a signal given, and the waiting van would arrive and take the prisoner away.

Eventually it was decided by Mick Collins that the Squad should go all out for the Igoe Murder Gang and to help us a Galway Volunteer, Sweeney Newell, was brought from somewhere in Galway – the actual town where Igoe had been stationed as a Sergeant in the RIC. Sweeney Newell knew Igoe very well and he was attached to our Intelligence Branch with Charlie Dalton to seek out and locate the Igoe Gang in Dublin and point them out to the Squad.

A number of tours of the city were made by the Squad, with Charlie Dalton and Sweeney Newell operating in front of us, but we failed to make contact with the Murder Gang. The strain imposed on the Squad by this class of work was rather great as it meant we were continually moving round the city from early morning – about 9 a.m. to 7 or 8 o’clock at night and our meals had to be taken wherever we could grab a sandwich and a cup of tea, and also because of the fact that we were more fully armed than usual, each of us being equipped with two revolvers, plenty of spare ammunition and a number of us with a couple of hand grenades. We had many exciting incidents moving around in this way and many opportunities of attacking the enemy which we found very difficult to resist but had to as our job was to concentrate on Igoe.

As Stapleton explained, shortly before Joseph Howley’s death, Volunteer Thomas ‘Sweeney Newell’ of Castlegar was selected by Michael Collins to help track down Igoe, whom his ‘Squad’ were keen to eliminate. Newell, however, was spotted by Igoe, and it is possible that Howley was killed by Igoe and his associates in the belief that Newell and others were on Igoe’s trail. Newell left the following account with the Bureau of Military History:

About the first week of November 1920, Baby Duggan [Thomas ‘Baby’ Duggan, IRA leader from Castlegar] came to me and told me that he had been to Dublin and that Collins was anxious that someone from Galway who knew Igoe well should go to Dublin and point him out to the ‘Squad’. I knew Igoe very well, as he had been stationed in Killeen for about six or seven years. I agreed to go to Dublin and point out Igoe. Baby Duggan accompanied me to Dublin. We were met near the Broadstone Station by Stephen Murphy who was a friend of Baby’s. Baby and I got digs on the North Circular Road. A day or two afterwards Baby brought me to see Collins. Stephen Murphy got me a job in the Dublin Whiskey Distillery, Jones Road. I worked from 7 a.m. till 1 p.m. I spent the evenings with the Active Service Unit.

After about three weeks I gave up the job in the Dublin Whiskey Distillery and went full time with the Active Service Unit. It was arranged that I would meet another member of the Active Service Unit at 9.30 each morning, near McBirney’s at O’Connell Bridge. Jim Hughes, who was also a member of the Active Service Unit, told me that the A.S.U. Headquarters was in Crow Street. I used to walk round various parts of the city each day with a member of the Active Service Unit. Different members of the A.S.U. used to accompany me, on the lookout all the time for Igoe. My companion was with me so that when we came across Igoe he could report back to A.S.U. Headquarters to give them the news where Igoe was and the direction in which he was proceeding, and I was to continue to follow him. I saw Igoe on two occasions, and my colleague reported to Headquarters as arranged but apparently there were no members of the A.S.U. available to take action.

At about 9.30 on the morning of the 7th January 1921, I was proceeding to meet my companion for the day at McBirney’s. When near McBirney’s I saw Igoe with about sixteen or eighteen others, in twos and threes, coming along the South Quays towards McBirney’s. I stepped into McBirney’s door so as to let them pass. Before reaching McBirney’s they turned into one of the side streets. My companion for the day had not arrived, so I followed them up the side street into Dame Street. They crossed Dame Street into Trinity Street and into Wicklow Street. In Wicklow Street I met Charlie Dalton and told him that Igoe and his gang had gone into Grafton Street. We both went back to Headquarters, Crow Street, where he reported the matter. Tom Ennis was standing outside Headquarters. After a few minutes Dalton came back and told me that he and I would walk on one footpath, and Hughes and Dan McDonnell would walk on the opposite path and that the Active Service Unit Squad would come along behind. I was not armed; Dalton was not armed either. Dalton told me that he thought that Igoe and his gang had gone to Harcourt Street Station to look out for IRA men coming off the country trains. We proceeded into Wicklow Street and were turning into Grafton Street when I almost collided with Igoe, who was returning from Grafton Street into Wicklow Street. I had gone only a few yards when I felt a hand gripping the collar of my coat. I turned round to see who was holding me. It was Igoe. ‘Come on, Newell’, he said ‘I want you’. ‘My name is not Newell’, I replied. ‘I know you anyhow’, said Igoe. Turning to one of his companions and pointing to Dalton, he said, ‘arrest that man’. We were then turned into Wicklow Street and continued along until we were opposite the Wicklow Hotel where we halted for a few minutes. I saw several members of the Active Service Unit including Tom Ennis, Frank Bolster, Joe Dolan, Tom Keogh and Flood, pass along on the opposite side and turn into Grafton Street.

We were again marched off into Dame Street where we were halted again. Igoe then questioned me as to who Dalton was. I said I did not know him and that he was not with me. Dalton was also being questioned. I did not hear the questions that were being put to him as we were too far apart. Igoe continued to question me. I realised the game was up and I said, ‘I know you, Igoe, and you know me’. I was then marched off, two of Igoe’s gang in front; one on either side of me, and two behind, until we arrived at a street junction of which I have since heard was Greek Street, where I was again halted. Igoe again questioned me as to how I came to be in Dublin, what was I doing there, where was Baby Duggan and many other similar questions, all of which I refused to answer. Four of Igoe’s gang were beside me and two on the opposite corner. Igoe said, ‘run into that street’, pointing to Greek Street. I said, ‘if you want to shoot me, shoot me where I am standing’. Then he gave me a hell of a punch which sent me several yards into the street, and immediately opening fire on me. I fell and I was not able to get up as I had received four bullet wounds, one in the calf of the right leg, two in the right, hip and one flesh wound in the stomach.

I then saw Igoe blow a whistle. Within a minute a police van arrived. I was thrown roughly into it and taken to the Bridewell. I was questioned as to where I lived in Dublin. I refused to tell them. I was beaten on the head with butt ends of revolvers, four of my teeth being knocked out and three or four others broke. I was left lying on the floor for some hours and was then taken in an ambulance to King George V Hospital. I was detained in King George V Hospital until December 1921. While there I underwent eleven operations. In December 1921, I was removed on a stretcher to the Mater Hospital, Dublin, and the following day I was operated on by surgeon Barnaville. In May 1922, I was allowed home for a month. I was still wearing a steel body jacket with a steel rod attached to it and running down to the heel.

Howley and Athy were not the only Volunteers in the Oranmore and Maree district to be killed during the period. Volunteer Patrick Cloonan, Ballinacloughy, Oranmore, was shot dead by crown forces near the home of a relative, Lawrence Donohoe, where he was staying on the night of 6 April 1921. He was a member of the Maree Company since its inception and served with Liam Mellows during Easter Week 1916. He was unmarried, aged 28 and a farmer. He was a member of the Oranmore Company of the Volunteers. It is probable that he was killed by members of D Company of the Auxiliaries with the aid of local RIC.

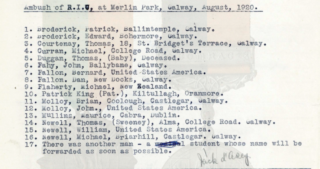

Participants in the Merlin Park Ambush, 21 August 1921

Patrick Broderick (Ballintemple); Edward Broderick (Bohermore); Thomas Courtenay (St Bridget’s Terrace); Michael Curran (College Road); Thomas ‘Baby’ Duggan (Castlegar); John Fahy (Ballybane); Bernard Fallon (later USA); Dan Fallon (New Docks); Michael Flaherty (later New Zealand); Patrick King (Oranmore); Brian Molloy (Castlegar); John Molloy (later USA); Maurice Mullins (later Dublin); Thomas ‘Sweeney’ Newell; William Newell; Michael Newell (all Castlegar). (Brigade Activity Report; Galway No 1 Brigade (MA/MSPC/A/21(3))

Primary Sources

Bureau of Military History, Witness Statement, William Stapleton (822).

Bureau of Military History, Witness Statement, Thomas ‘Sweeney’ Newell (698).

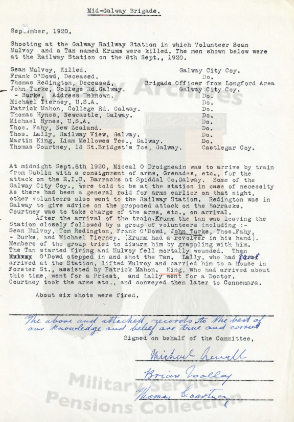

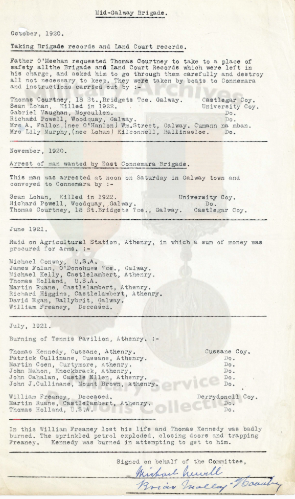

Brigade Activity Report; Galway No 1 Brigade (MA/MSPC/A/21(3)); Military Archives.

Military Service Pension Applications: Michael Joseph Howley (1D402); Joseph Athy (DP635); Patrick Edward Cloonan (DP25208).

Further Reading

William Henry, Blood for Blood: The Black and Tan War in Galway (Mercier Press, 2001).

Conor McNamara, War & Revolution in the West of Ireland: Galway 1913–22 (Irish Academic Press, 2018).

Conor McNamara, The Loughnane Brothers, Beagh and Terror in Galway, 1920–21 (Galway County Council, 2020).

Conor McNamara, The Independence Struggle in County Galway, 1918–21, A Research Guide (Galway County Council, 2021).

Timothy McMahon (ed.), Pádraig Ó Fathaigh’s War of Independence (Cork University Press, 2000).

Cormac Ó Comhraí & K.H. O’Malley (eds), The Men Will Talk to Me, Galway Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Mercier Press, 2015).

Cormac Ó Comhraí, Sa Bhearna Bhaoil: Gaillimh 1913–1923 (Cló Iar-Chonnacht, 2016).

No Comments

Add a comment about this page