Patrick (Pádraig) Pearse in Rossmuck

A glimpse into 1916 Leader Padraig Pearse's relationship with the Connemara Gaeltacht

by Hilary Kiely

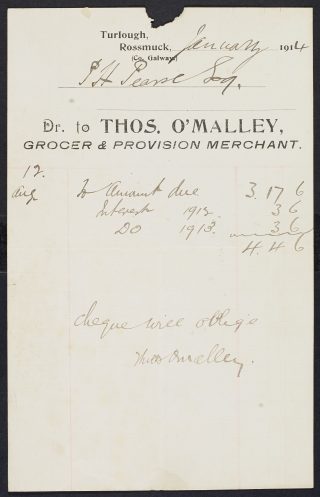

Residing in the collection of Padraig Pearse’s papers in the National Library of Ireland is this small slip of paper (image at right). Small though it is, this invoice from O’Malley’s Grocer & Provision Merchant reveals something of Pearse’s relationship with Connemara and with with money, both of which were nearly as much a hallmark of Pearse’s personality as his revolutionary ideology. Before his fateful reading of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic in front of the General Post Office in Dublin on Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, Pearse had been an educator, an editor, and an examiner for Conradh na Gaeilge (the Gaelic League).

It was in his role as an Irish language examiner that he was first to come to Rosmuc in Galway’s Connemara Gaeltacht. In 1903 he was sent from Dublin to administer an exam for students to qualify as a teacher of Irish (you can read an account of his first encounter here: “The Stranger Standing at Maam Cross Station”). He would go on to visit the area every year for the rest of his short life and by 1910 had built here a three room cottage. This would serve as a refuge for him, and a precursor in a way of the modern student’s Gaeltacht immersive summers, as he brought students out for summer trips from St. Enda’s, the Rathfarnham school he founded.

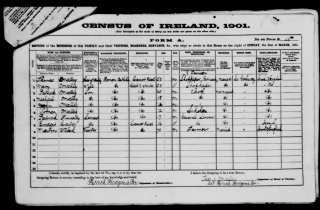

It was to this sanctuary that he retreated in 1915 when asked by fellow revolutionary Tom Clarke to deliver a speech at the funeral of Fenian leader Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa, whose remains returned to Ireland from the USA after his years in exile. Pearse’s friend Desmond Ryan, who along with Padraig’s brother Willie accompanied him, recounted this Connemara excursion in his own autobiography, Remembering Sion. He mentions that is a member of the O’Malley family, “who were famous in those parts”, that picked them up at Maam Cross Station and drove them by side-car the nine miles to Rosmuc.[i] We can see by the 1901 census return of our shopkeeper, that Thomas O’Malley had a number of sons, any of whom may potentially have been the driver.

These were not the only republicans to spend time in this cottage and encounter O’Malleys that summer, as Pearse extended an offer of the cottage to the siblings of fellow Proclamation signatory Joseph Mary Plunkett. Geraldine, Fiona, and Jack Plunkett would idyll here as well in 1915. From O’Malley’s they got eggs and cocoa and baskets of fish, as well as their post − which included a postcard from Pearse telling them not to mind any demand for rates, as he had no intention of paying (and every intention of the O’Malley’s seeing the message!)[ii] We can see by the invoice that Pearse has a history of owing money to O’Malley’s Grocers. The bill is for provisions from Thomas O’Malley Grocer& Provisions Merchant. What the goods purchased were is not specified, but the original purchase was made in 1912, and as of 1914 remained unpaid and accruing interest, the debt in today’s money amounting to nearly €290.

And the O’Malley’s were not the only ones in the area whom Pearse left out of pocket. It was put this way in the 1978 radio documentary aired on RTÉ: “Pearse was not a practical businessman, but he was never one to let lack of finances get in the way of his plans.”[iii] As related to Tim Robinson by Proinsias MacAonghusa in Connemara: A Little Gaelic Kingdom:

“Probably he was not able to meet the bills; he was a man who always had very little money and faced heavy expenses in many places. He was summonsed for this in Oughterard court. I believe the bill had not yet been cleared when the British Government put him to death. But it is the man himself and his ideas and ways of life that impressed Ros Muc, not the thinness of his purse” [iv]

According to Robinson, the local tradespeople who built the cottage can still be named locally today (or could anyway when the book came out in 2012). Pearse’s connection to the place has been little diminished by time and his absence. The locals understood he was not a wealthy man, only rich in ideals and intellect, and charged him accordingly or often let the debt ride. The esteem and goodwill with which he was held is evident in the fact that the O’Malleys continued to provide provisions to Pearse and his guests years later − and Thomas O’Malley was still willing to take a cheque.

A poignant postscript to the story of the speech Pearse wrote in Connemara that did not make it into the final published version of Remembering Sion is that on that very evening after the electrifying graveside speech in 1915 at Rossa’s funeral, having delivered the immortal words, “Ireland unfree shall never be at peace”, the penniless Pearse had to borrow ten shillings from Desmond Ryan.

For further information:

“Preparing to Speak to History” https://www.rte.ie/centuryireland/index.php/articles/preparing-to-speak-to-history

References:

[i] Desmond Ryan, Remembering Sion, Dublin, 1934.

[ii] Galway Advertiser, “Pearse did not want its beauty to be wasted”, May 19, 2016, https://www.advertiser.ie/Galway/article/84859/pearse-did-not-want-its-beauty-to-be-wasted

[iii] O’Conluain, Proinsias. Documentary on One: This Man Had Kept a School, radio documentary aired 1978 https://www.rte.ie/radio1/doconone/2012/1025/647221-documentary-podcast-scoil-eanna-school-bilingual-pearse/

[iv] Robinson, Tim. Connemara: A Little Gaelic Kingdom, Dublin: Penguin Publishing, 2012, pg 29

[v] Ryan, Desmond. Remembering Sion typescript, Ryan Papers, UCD, LA10/341

Comments about this page

Here is a picture of Thomas O’Malley and his wife Mary Corbett

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/102556572/tomas-%C3%B3_m%C3%A1ille?fbclid=IwAR1IyO9tJoAg4CzSdWHlxnXddKpi7EjySUDuD-MebPWK4_dmxUbjWSlAM8o

What a wonderful image and great addition to the information here. Many thanks.

Add a comment about this page