On the Hillside: The West Connemara Flying Column & the War of Independence, 1921

Revolution in County Galway, 1918-23

Dr Conor McNamara, Historian-in-Residence, 2022

The Connemara Volunteers were divided into two battalions in August 1920, with the East Connemara Battalion led by Micheál Ó Droighneáin of Spiddal, and the West Connemara Battalion, initially, led by Colm O’Gaora of Rosmuck, with P.J. McDonnell, Leenane, taking over the leadership of the battalion in late 1920. Meetings were frequently held at the home of West Galway MP Pádraic Ó Máille at Muintir Eoin near Leenane. The nucleus of this group went on to form the West Connemara Flying Column in 1921 and initially consisted of members of the Leenane company under Pádraic Ó Máille, the Rosmuc company under Colm Ó Gaora, the Roundstone company under Jim King and the Clifden company under Gerard Bartley. This column carried out three lethal attacks on the police and used their knowledge of the mountainous terrain to evade capture until the truce in July 1921.

By the end of 1920, Volunteer officers in County Galway were increasingly unable to stay in their own homes and were forced to go on the run to avoid arrest or assassination by crown forces. The police noted in November:

A good deal of sympathy among people with a stake in the country is due to fear and there are indications of a return to sanity and revulsion against Sinn Féin on the part of the more respectable people, now that the government are beginning to get a grip on the situation. As far as Galway is concerned Sinn Féin has largely lost its power.

The RIC reported to their superiors that they were beginning to receive valuable information on the activities of the Galway Volunteers, claiming “the feeling toward the police is much better with the people inclined toward friendship and there is no attempt anywhere to boycott them. I have received bone-fide information of two or three ambushes prepared for the police.” In March 1921, the West Galway police reported:

The IRA are now confined to the outlying, backward areas where Sinn Féin still lives. There is a bitter undercurrent of hatred against the government and Crown Forces. If the present pressure was relaxed, Sinn Féin would once again renew its old sway in a more rigorous and determined manner. It had such a reign of terror that it will take a long period to remove its evil and ruinous affects.

In January 1921, the West Connemara Flying Column was formed at meetings in the Ó Máille farmhouse, Muintir Eoin, attended by West Connemara’s leading republicans. There were almost fifty men in the column at various times, hailing from the districts of Leenane, Rosmuc, Roundstone and Clifden. Commander of the column, P.J. McDonnell of Leenane, explained the group’s motivation after being unexpectedly summoned before an audience with the Archbishop at Clifden:

The police and military of England were roaming the country to try and exterminate anyone who stood for freedom of their country; that they pulled men out of their homes and shot them on the street, sometimes before the eyes of their families and that any man who had a chance of fighting was a fool if he waited to be pulled out and shot without making an effort to fight back.

Many more men wanted to join the column than could be accommodated in the unit and Volunteer Jack Feehan recalled: “twice the number turned up to what we expected, and each man had his own small contribution, such as a shotgun, gelignite, cartridges. They obtained gelignite while working for the County council. It was sad to turn some of these men away, for we only had accommodation for twenty.” (BMH/WS 1,692; Feehan)

William King recalled: “the flying column provided itself with blankets and bedding by commandeering them from imperialist families including that of Lord Sligo at Ashleagh. They went to Glanmigla for about a week’s training which included scouting, judging distance, aiming, rifle drill and all aspects of cover from view and fire. There was no target practice as ammunition was too spare.” (BMH/WS 1,731; King, p. 10)

As the column could only fully equip twenty men, the unit was limited in size and was fully mobilised on 10 March at Aille na Breagh (Aille na Veagh), at the back of Diamond Mountain, 11 kilometres (seven miles) east of Clifden. The site was chosen as it was in easy striking distance of Clifden and offered a vantage point over both roads leading out of the village. The Connemara landscape posed unique problems as McDonnell recalled: “the roads in Connemara are like the country ‘bare and bleak’ with no sheltering walls where shotguns would get within range of the enemy”. The Clifden battalion was responsible for arranging food supplies to be dropped near the unit’s base and the Leenane company was responsible for keeping the hide-away in battle readiness.

The column was composed of Volunteers with no experience of guerrilla warfare and, as McDonnell recalled: “until they had their first fight, that with the exception of the quartermaster and myself, not a man of the column had fired a shot out of a service rifle”. Food occasionally ran out and the column experienced several prolonged periods living off tea and the meagre kindnesses that poor families in isolated communities could offer. The conditions took their toll and Jack Feehan recalled that “four days under such terrible conditions was telling on the younger men”.

Attack at Clifden

The column killed two RIC men in their first attack, carried out in the town of Clifden on the night of 16 March 1921; Constable G.C. Reynolds died instantly and Constable Thomas Sweeney died after his right leg was amputated. The attack was carried out in revenge for the execution of Thomas Whelan in Mountjoy Gaol the previous day. Whelan, who was originally from Clifden, was hanged for his alleged part in the killing of a state agent in Dublin in November 1920, and according to Jack Feehan: “We felt it our duty to avenge his death.”

On arriving into the village, the unit spotted six RIC men and selected six men of the column to attack the group, with the remainder holding the barracks under fire; Feehan recalled: “It was decided to pick six of the best shots. We thought it fair enough – man to man, six enemy to six IRA.” When fire was opened by the group, only two RIC were visible and both were killed. The column retreated and in the hours after the attack, at least sixteen houses were burned by crown forces and hundreds of young men were arrested. A civilian ex-serviceman, J.J. MacDonnell, was shot dead after calling to the police station to appeal for help in dousing the flames engulfing his father’s hotel.

Following the attack, it was decided to move the column to the Maam Valley to escape the attentions of the police and attempt an attack on Maam police station, the only other permanent police barracks in Connemara. Travelling across the Twelve Bens Mountains, the column camped at Glencraff, a valley 6.5 kilometres (four miles) west of Leenane, before making for the Ó Máille homestead, Muintir Eoin, half way between Leenane and Maam and 6.5 kilometres (four miles) from the police barracks. Travelling across the mountains with little food was difficult for the toughest of fighters and, according to Jack Feehan: “To be alone and to have lost one’s way in these mountains on such a night would be to court death from exposure.”

After a few days’ rest, McDonnell decided that a successful attack on the Maam barracks was not a realistic possibility given the reinforced nature of the building and the little ammunition at the unit’s disposal. It was decided instead to try and ambush a patrol of RIC and the unit departed on 4 April, crossing the Maamturk and Oorid mountains to Gortmore in the Rosmuc district of southwest Connemara. The column billeted at an ambush spot on the Maam Cross–Screebe road and took some hard-earned rest while local Volunteers stood watch. On 6 April, the column attacked a party of five RIC men travelling by bicycle at a location adjacent to Screebe Church where they knew the police passed each week to pay a local RIC pensioner. Feehan claimed the ambush was the unit’s personal act of revenge for the killing of Galway priest, Fr Michael Griffin, by crown forces in November 1920. The ambush was a partial success as one policeman, William Pearson, a native of New Zealand, died from his wounds. An RIC man who lay prone in a ditch was spared as he begged for mercy, while his comrades escaped on foot; some of whom took shelter at nearby Screebe Lodge. Volunteer George Staunton was disappointed with the outcome of the ambush, claiming “one over anxious member of the column fired a shot on the impulse of the moment which upset the whole target”. (BMH/WS 453; George Staunton) P.J. McDonnell was incensed, insisting that a member of the group fired too early and ruined their chances of inflicting a major blow. After failing to locate the escaped policemen, the column collected the RIC’s weapons, along with several bottles of poitín; McDonnell destroyed most of the bottles, keeping two for ‘medicinal purposes’.

Following the attack, the crown forces burned a number of cottages in the vicinity, including that of Volunteer Colm Ó Gaora, Patrick Pearse’s holiday cottage, the co-operative store in Camus and the home of the local school teacher. Volunteer Thomas Geoghegan, who joined the men after the ambush, appears to have suffered a breakdown after learning of the destruction of his family home and, according to McDonnell: “he went completely out of his mind. It took about four men to control him and get him upstairs, put him lying on a bed and tie him down to it. We sent to Leenane to get the doctor … he came along and gave him an injection of morphia which quieted him down.” (BMH/WS 1,612; P.J. McDonnell)

Gun battle at Muintir Eoin

Following the engagement at Clifden, life became harder for the column; as George Staunton explained:

It would be foolish to remain in the one place for any length of time and to look for any kind of comfort was out of question. Any rest we had was during the daytime, for at night time we did all the travelling. Furthermore, a stranger in a strange place would be spotted and talked about if seen by the neighbours, who I must say this for them, wouldn’t wish anything harmful to happen to us, but there was the danger that the wrong person would get to know things ending up in causing us unpleasantness. (BMH/WS 453; George Staunton)

Needing to send money to GHQ to attain more weapons and ammunition, the unit decided to levy a tax on farmers in the district; as Feehan explained: “we levied a certain sum on each farmer, knowing that he could afford the amount levied”. Some rich pickings were exploited and Kylemore House, the home of Colonel Mark Clifden, was raided and weapons and clothes taken.

The Ó Máille family homestead, Muintir Eoin, in northwest Connemara was the scene of the column’s final engagement on 23 April. Muintir Eoin was the well-known homestead of one of the leading republican families in Connemara and would inevitably be raided. The men were aware, however, and decided to lay in wait for the inevitable fight; as McDonnell later explained: “every man of the column was anxious to have a really good fight and justify our existence as a fighting unit”.

The attack finally came when police arrived for a routine raid. The Volunteers assumed their pre-planned ambush positions and awaited their orders to open fire; however, a premature shot alerted the police to the attacking party and the advantage was lost. McDonnell recalled: “once again the element of surprise was destroyed despite all my instructions. No man owned up to having accidently or deliberately discharged his rifle.” In driving rain both parties took cover and engaged in sporadic shooting, neither side able to win a decisive advantage. Jane Ó Máille and her two young children remained in an outhouse as over forty armed men fought a gun battle around her. After almost twelve hours of exchanging fire, and several men wounded and constable John Boylan killed, a line of police lorries became visible on the horizon. As reinforcements dismounted and the column was almost completely out of ammunition, the Volunteers fled and police burned the Ó Máille property.

Following the battle, the column made its way north to the townland of Townaleen, west of Shanafaraghan near Lough na Fooey, “a quiet lonely place” according to Feehan. Camped out among the elements in a canvas tent, on the remote northern side of Killary Harbour, the remaining eighteen men received the sacraments from the same priest who had ministered to the RIC during the previous gun-battle. With the days getting longer, the north Connemara district was increasingly patrolled by large convoys, while a spotter plane patrolled the skies. The column’s life became more difficult and they were increasingly forced to concentrate their energies on evading capture and destroying bridges, a laborious task, carried out with pick and shovel.

Aftermath of the Battle

Following the battle at Muintir Eoin, William King was captured in a round-up by crown forces:

I had come home for one night and was captured at home. I was taken to Maam RIC barrack where I was badly beaten. Shots were fired over my head, pins were driven into my skin and all sorts of threats used by the RIC to ask me tell the whereabouts of my brother John C. Towards evening after a day of torture, one of the RIC named Mallane came to me in my cell and that later on when all the other RIC and Tans would get drunk, he would help me to escape through the back gate. He was as good as his word and in spite of all the beatings and the torture I got away from the place very quickly and swore that I would never be caught again. (BMH/WS, William King, p. 17)

During the final weeks of the campaign, the column had sixteen rifles and around 200 rounds of ammunition, and was firmly on the defensive. Remarkably, P.J. McDonnell took a day off to get married, his comrade, Jack Feehan, acting as best man. The ceremony took place at Kilmeena Church in south-west Mayo on 17 May, both men being armed with grenades and pistols. Neither groom nor best man got to enjoy the celebrations and both returned to join the column later that evening.

Having to guard against being captured, the unit was broken into smaller units on 9 May 1921, with one group under Jack Feehan moving into South Mayo, while the remaining members were forced to levy farmers in north Connemara to purchase supplies. Feehan recalled: “we had to make demands sternly, as this area was a poor one and money was hard fought”. After receiving ammunition from GHQ at the beginning of June, it was decided to try and join the West Mayo column and launch an attack near Leenane. A navy destroyer lay at berth in Killary Harbour, a military aeroplane flew continually overhead and large convoys traversed the narrow roads of north Connemara.

The men’s religious faith remained important to them during their time on the run and Martin Connelly recalled that following the battle at Muintir Eoin:

While in the camp, we expressed a desire to go to confession and receive holy communion. The O/C arranged with Fr Cunningham to come to the house of Michael Wallace, which was just across the narrow inlet of the Bay that I mentioned earlier. His house was always at our disposal and was used as a depot for receiving food, messages, etc, while we were in the area. He had two sons in the column – Peter and Patrick Wallace. Next night, Fr Cunningham came at night. We all got confession and received holy communion. Peter Wallace and another man then ferried the priest across the narrow channel and escorted him to Leenane. (BMH/WS. Martin Connelly, p. 17)

Despite their sincere personal religious convictions, the Galway flying columns faced considerable clerical condemnation. At the height of the conflict in March 1921, Archbishop Thomas Gilmartin of Tuam expressed his solidarity with the people of Galway, “in their feelings of horror and indignation at the actions of the crown forces”. However, the Archbishop went on to warn his flock against channelling their anger into support for the Volunteers’ campaign as “what is called the IRA may contain the flower of Irish youth, but they have no authority from the Irish people or from any moral principle to wage war against unequal forces with the consequence of terror, arson and death to innocent people”.

The column’s final days were spent in the north-western hills of Connemara and the unit were at a location named Glennagimla with a group of Mayo officers when news of the truce that ended the conflict arrived; Jack Feehan recalled: “there we received a splendid welcome from our friends and were united with them amid tears of joy, thanking God that we were safe and happy”. In terms of their military struggle with the crown forces, there was some disagreement as to how strong a position the IRA were in when the truce was announced in July 1921. P.J. McDonnell recalled: “I cannot say that we went wild at the news. To say we were stunned would be nearer the mark, until it began to sink in that the British had been forced by men just like us fighting all over the country to agree to a truce.”

The hardship of fighting in such inhospitable territory had taken a toll on the health of a number of the men. Two Volunteers were invalided with severe burns from boiling water, William Connelly shot himself in the leg, Colm Ó Gaora had suffered facial paralysis, Thomas Geoghegan experienced a breakdown and a number of men had suffered a variety of lesser injuries. William King recalled:

A few days before the truce, Padraig O’Maille received a summons to Dublin for a meeting of Dáil Éireann. “Remember Bill”, he said, “if ever anything comes of this truce with England, I’ll see that all my comrades will be looked after.” But that’s as far as promises went. Some of my old comrades of the IRA are now gone to their reward. Some are in exile and scattered to the four winds of the world. They were fine boys and loyal comrades but the cause for which they fought is still there with the fight unfinished. I pray to God to have mercy on my dead comrades and I pray that Ireland will have her freedom as Pearse wanted it – not merely free but Gaelic as well, not Gaelic merely, but free as well.

Throughout 1921, it was far from clear who was winning the battle between the crown forces and the Volunteers in Galway. The truce was viewed as a welcome return to normality by most and for republicans as a chance for a well-earned rest. It was widely believed that peace would not last long, negotiations would break down and violence would erupt once more. The retrospective notion that the military stalemate of the summer of 1921 represented a victory for the IRA would have been viewed with scepticism.

Aftermath

Disbanded following the truce and subsequent treaty, almost every original member of the West Connemara Flying Column took the anti-Treaty side during the Civil War and Clifden was to be the scene of intense fighting on several occasions between the West Connemara Brigade and the National Army. The Brigade linked up with Michael Kilroy and Thomas Maguire in West and South Mayo, making West Galway and Mayo a republican stronghold.

During the Truce period, P.J. McDonnell continued to serve full time as an IRA officer and in March 1922 he became Divisional Vice Officer Commanding the 4th Western Division. During the Civil War he took part in a number of engagements with the National Army in Galway and Mayo, including at Clifden (October 1922), Newport (November 1922) and Delphi (December 1922). He was captured on 24 May 1923 and tried and sentenced to death, subsequently commuted to penal servitude – and held until 12 July 1924 at Galway Jail, Tintown and Hare Park internment camps.

Gerald Bartley, who was born in an RIC barracks, the son of a police sergeant, became a Fianna Fáil TD between 1922 and 1927 and again between 1927 and 1965. He first went to school in Clifden before being educated in O’Connell’s school in Dublin where he joined the Dublin Brigade of the IRA. Like many of the column’s senior members, he took the anti-Treaty side during the civil war and was imprisoned in Galway, Belfast and Dublin. He subsequently served as Minister for the Gaeltacht in 1959 and Minister for Defence in 1961.

Elected to Dáil Éireann in 1918 and in 1921 and 1922, Pádraic Ó Máille was one of the few members of the column to accept the Treaty and was appointed Leas Ceann Comhairle in 1922, a post he retained until 1927. From May to June 1922, he was one of the ten-member committee, comprised of an equal number of pro- and anti-Treaty TDs charged with averting civil war. He was also a member of the subcommittee formed to draft the constitution of the Cumann na nGaedheal in September 1922. On 7 December 1922, he was shot in the spine outside the Ormond hotel in Dublin, accompanied by Senior pro-Treaty leader Seán Hales, who was killed in the attack. It was believed that Ó Máille was the intended victim, owing to his vote in favour of the special powers resolution that paved the way for the execution of IRA prisoners. In 1926, together with Professor William Magennis, he formed a new constitutional republican party, Clann Éireann. The party sought the abolition of the oath of allegiance to the Queen, the revision of the boundary agreement and the pursuance of a policy of protectionism. He was defeated in the June 1927 election and elected to the senate as a Fianna Fáil representative in 1934; he remained a senator until his death on 19 January 1946.

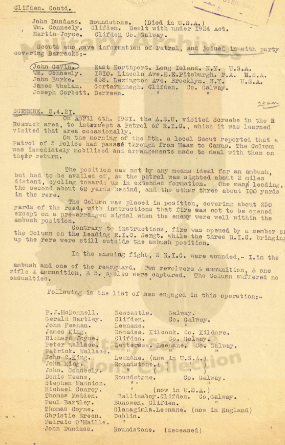

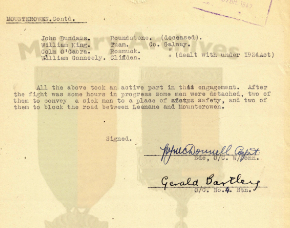

West Connemara Flying Column members, 10 March 1921 (34 members)

Leenane (12): P.J. McDonnell; John Feehan; Martin Connelly; John King; Michael Joyce; Willie King; Peter Wallace; Patrick Wallace; John Faherty; John Coyne; John King; Thomas Coyne.

Muintir Eoin (1): Padraig Ó Máille.

Clifden & Ballinaboy (11): Richard Joyce; Gerald Bartley, Paul Bartley; Christy Breen; Thomas Madden; Martin Joyce; John Gavin: William Connelly; Thomas Burke; John J. Connelly; John King.

Roundstone & Calla District (6): Denis Keane; John King; John Connelly; Michael Conroy; Stephen Mannion; John Dundass.

Tullycross District (3); Patrick McDonnell; Laurence O’Toole; Patrick Keane.

Westport (Co. Mayo) (1): William Connelly.

Seven additional members who joined on 4 April 1921:

Rosmuck District (4): Colm Ó Gaora; Patrick Nee; Michael O’Donnell; Patrick Geoghegan.

Kilmilkin District (3): Charles O’Malley; Eamonn Ó Máille; Tomas Ó Máille

Six additional members who Joined on 1 May 1921:

Cornamona District (3): Michael Browne; Michael Joyce; Michael Coyne.

Lettermore District (1) George Staunton.

Carna District (1) Michael Lyden.

Maam District (1) Thomas O’Malley.

Primary Sources

Bureau of Military Witness Statement, George Staunton (453).

Bureau of Military Witness Statement, P.J. McDonnell, Leenane (1,612).

Bureau of Military Witness Statement, John C. King, Leenane (1,731).

Bureau of Military Witness Statement, Martin Conneely, Leenane (1,611).

Bureau of Military Witness Statement, John Feehan, Leenane (1,692).

Brigade Activity Report, West Connemara Brigade, 4th Western Division (MS/MSPC/A36 3); Military Archives.

Further Reading

Jarlath Deignan, Troubled Times: War and Rebellion in North Galway, 1913–23 (Jarlath Deignan, 2019).

William Henry, Blood for Blood: The Black and Tan War in Galway (Mercier Press, 2001).

Conor McNamara, War & Revolution in the West of Ireland: Galway 1913–22 (Irish Academic Press, 2018).

Conor McNamara, The Loughnane Brothers, Beagh and Terror in Galway, 1920–21 (Galway County Council, 2020).

Conor McNamara, The Independence Struggle in County Galway, 1918–21, A Research Guide (Galway County Council, 2021).

Cormac Ó Comhraí & K.H. O’Malley (eds), The Men Will Talk to Me, Galway Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Mercier Press, 2015).

Cormac Ó Comhraí, Sa Bhearna Bhaoil: Gaillimh 1913–1923 (Cló Iar-Chonnacht, 2016).

Colm Ó Gaora, Mise (Oifig an tSoláthair, 1944).

Mícheál Ó hAodha, Ruán O’Donnell (eds), On the Run, The Story of an Irish Freedom Fighter, A Translation of Colm Ó Gaora’s Mise (Mercier Press, 2011).

No Comments

Add a comment about this page