The Lonesome Death of Fr Michael Griffin: Galway's Martyred Son

Revolution in County Galway, 1918-23

Dr Conor McNamara, Historian-in-Residence, 2022

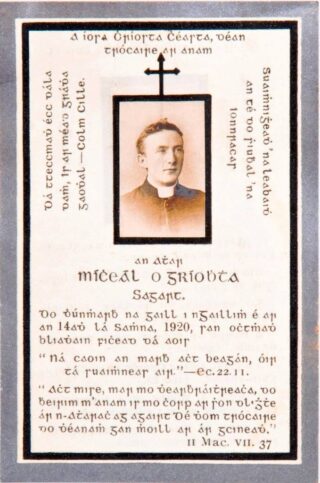

Fr Michael Griffin was one of only three priests to be killed by crown forces during the War of Independence. He left the parochial house on Sea Road, Galway City, on a sick call after a local man, who was known to him, called to the house on the night of Sunday 14 November 1920; he was never seen alive again and his body was recovered the following week in the Bearna district. He had been shot in the head and his body was dumped in a field, covered by soil. The killing caused a sensation across Ireland and Fr Griffin’s funeral was one of the largest ever held in County Galway; his body was interred in the grounds of Loughrea Cathedral. The killing sparked widespread fear and revulsion in Galway and suspicion immediately fell on D Company of the Auxiliaries based in Lenaboy House in Salthill – aided by at least one local man and elements of the regular RIC.

Fr Michael Griffin was born in 1890 in Gurteen in north Galway and was ordained a priest in Maynooth in 1917. Officially a priest of the Clonfert Diocese, Fr Griffin was loaned to the Galway Diocese and was initially appointed to a curacy in Ennistymon, County Clare, before being transferred to Rahoon Parish, which comprised St Joseph’s Church on Sea Road and Bearna Church, along with the districts of Rahoon and Bushy Park. Fr Griffin was a keen member of the Gaelic League and an enthusiastic supporter of the independence movement, and he frequently contributed to public meetings in Irish. A popular and charismatic figure, the Freeman’s Journal noted

Of a genial disposition, Father Griffin was the soul of good nature. The esteem in which he was held was revealed in the indignation that has been expressed at his abduction. Catholic members of the RIC are shocked at the occurrence. (Freeman’s Journal, 17 November 1920, p. 5)

It was initially believed that Fr Griffin was being held prisoner in Lenaboy barracks by D Company of the Auxiliaries in revenge for the earlier disappearance of Patrick W. Joyce, a school teacher from the Furbo district who was kidnapped and shot as an informer by the East Connemara Brigade IRA. Joyce had made little secret of his antipathy towards local republicans and had campaigned to have Micheal Ó Droighneáin, a republican officer from Spiddal, removed from his post as a primary school teacher. Joyce’s fate was sealed when letters he wrote to the police, outlining Ó Droighneáin’s movements as well as allegations against other Volunteers, were intercepted by Volunteer Joseph Togher in the Galway Post Office. Ó Droighneáin formally asked Volunteer GHQ for advice as to what steps to take as “he did not want to have the responsibility of taking appropriate action in such a case”. Volunteer John Geoghegan, who was later shot dead by the crown forces, was formally ordered by Volunteer leader Richard Mulcahy to have Joyce executed. In the interim, three more of Joyce’s letters were intercepted by Togher, addressed to the officer in charge of Renmore barracks, the officer in charge of the 17th Lancers at Earl’s Island, and a third to the Chief Secretary’s office. Upon receipt of the second batch of letters, Ó Droighneáin had a priest brought to a disused cabin between Barna and Moycullen and Joyce was taken from his home by masked men with a canvas bag placed over his head. He was ‘tried’ by a three-man Volunteer court, convicted, taken into the bog, shot dead and buried in a shallow grave.

In the aftermath of Joyce’s disappearance, the local community displayed little sympathy and the police noted: “we have not alone received no assistance, but in some instances the attitude of those questioned has been insolent and defiant”. The crown forces frantically searched districts west of the city, with civilians beaten and property damaged. Notices were pinned up in Eyre Square stating that, if Joyce was not returned: “somebody would be made to pay the penalty” – that somebody was to be Fr Michael Griffin.

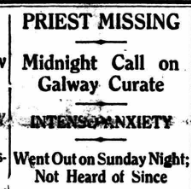

On the night of 14 November 1920, an unknown person, accompanied by at least two men, called to the parochial house shared by Fr Griffin and Fr J.W. O’Meehan on Sea Road. Fr O’Meehan was not sleeping at the house at the time, owing to threatening letters he had been receiving. After a conversation in Irish with the caller, Fr Griffin departed on what he thought was a sick call to one of his parishioners and he was not seen alive again. Suspicion fell immediately upon the local Auxiliaries stationed at Lenaboy House in Salthill but the local District Inspector of RIC, Cruise, told reporters that he “was confident that no member of the Crown Forces had anything to do with the abduction”. (Freeman’s Journal, 17 November 1920, p. 5)

Fr Griffin’s housekeeper later testified to reporters that three men called to the parochial house amidst heavy rain and gale-force winds shortly after midnight on Sunday. The men were later described as wearing trench coats and rubber boots and were described by the housekeeper as speaking “in ordinary tones”, alluding to the widespread belief that Fr Griffin assumed he was going on an urgent sick call. However, it was noted that he did not take the Blessed Sacrament with him, as would be the case when called to dispense the last sacraments. It was also believed that Fr Griffin took refuge from the storm with some other priests, but when he failed to return home, Fr Peter Davis noted that “no Catholic or no Irish man would touch a hair on the head of Fr Griffin”. (Freeman’s Journal, 17 November 1920, p. 5)

Following the disappearance, local people, organised by the clergy, searched the countryside to the west of the city and tension began to appear between local Catholic members of the RIC and the Auxiliaries and Black and Tans. The Freeman’s Journal noted that:

Local Catholic members of the RIC discussed the question of making a direct protest to the Bishop against any insinuation that they were in any way responsible for, or privy to, the abduction of a Catholic priest, which they deplore as deeply as anyone. (Freeman’s Journal, 19 November 1920, p. 4)

A local police officer informed the Freeman’s Journal that “whilst they would welcome the assistance of civilians who would conduct a search under police control, we could not tolerate any body of men usurping our functions.” (Freeman’s Journal, 19 November 1920, p. 5) Meanwhile, Joseph Devlin, senior MP with the Irish Parliamentary Party and MP for Belfast West, tabled a question in the House of Commons, asking the chief secretary of Ireland whether his attention had been called to the case.

Six days after he disappeared, a search party of parishioners found Fr Griffin’s body, buried under rough ground near Bearna village. He had a gunshot wound to the head. Micheál Ó Droighneáin recalled: “the priests came out and, with the aid of lanterns, the clay was removed with spades and shovels, and the body taken up; later that night, the body was placed on a donkey cart and brought in”. The Freeman’s Journal noted: “The discovery was made when a piece of clerical garb, thought to be the tails of a priest’s overcoat, were discovered a couple of hundred yards from the roadside at Claughskella near Lough Inch, four miles from Galway. By the light of a lantern, the soil was reverently dug up by parishioners, and Fr Griffin’s body found.” (Freeman’s Journal, 22 November 1920, p. 5) Fr W.J. O’Meehan and several other priests were notified of the find and immediately rushed to the scene; Fr O’Meehan later recalled finding the body:

Presently, one of the boys who was down in the mud searching carefully with his hands, speaking almost in a whisper said: “I have found a priest’s collar Father. Here is poor Fr Griffin.” I put my hand down and laid it on the collar and neck of my beloved comrade. The men drew away and there was a suppressed moan, followed by exclamations of horror. (Freeman’s Journal, 22 November 1920, p. 5)

The police in Galway and the authorities in Dublin Castle continued to deny any culpability for the murder, despite widespread belief that the Auxiliaries were responsible. Galway TD Pádraic Ó Máille wrote to the national papers, calling Fr Griffin a “saintly and true-headed Irishman”:

It is well known that Fr Griffin’s death is not due to the action of any section or portion of the Irish people. If any member of the English government challenges this statement, we are prepared to leave this and similar atrocities to be investigated by a commission composed of equal numbers from the Irish Republican and English governments, together with three representatives selected by either the governments of the United States, France or Italy. (Freeman’s Journal, 27 November 1920, p. 7)

As the body of Fr Griffin was being brought back into the city, tensions were high and a row of thatched houses was burned by the police as the clergy refused to give possession of the remains to the crown forces. Fr Griffin’s body was subsequently brought to St Joseph’s Church and reposed upon the altar where thousands of Galwegians queued for hours to pay their respects. University College Galway took the unprecedented step of closing for a day to allow students to visit the remains. It was noted that several members of the RIC and 17th Lancers accompanied the local Protestant Rector to the altar. (Freeman’s Journal, 23 November 1920, p. 3) Meanwhile, the official military inquiry into the killing was boycotted by Fr Griffin’s housekeeper, Ms Barbara King; however, William Mulveagh, a neighbour, testified that three men in trilby hats and raincoats had called to Fr Griffin on the night of his disappearance and that a car passed through Salthill twenty minutes later.

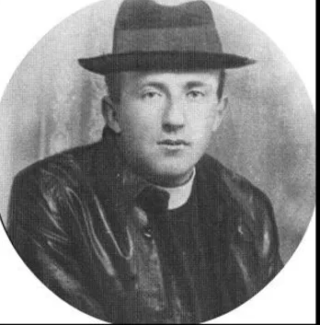

The Galway Volunteers were concerned about the activity of civilians who they believed were passing information on their activities to the crown forces in Galway City. The Galway Brigade sent a secret document to Michael Collins’ intelligence department in Dublin in 1920 marked “Suspects and Enemy Agents”, listing the details of twenty-six men in the city who they believed were acting as spies. Among the list appears the name W.P. Joyce with the note: “son of Joyce, manager of Tramway Company. Proved Spy. Is very active. He is in touch with both military and police and apparently is detailed for specialised work. He has organised a section of youths from 16 to 19 years of age who act as observers, etc.” The memorandum lists the details of four young men from the Shop Street and Eyre Square area of Galway City. William Joyce was well known in the town for associating with the crown forces and had been seen accompanying them on their raids, helping them navigate the small local roads and identifying local people.

It was popularly believed that the caller who lured Fr Griffin to his death was indeed by this local man, William Joyce – no relation of the aforementioned Patrick Joyce, killed by the East Connemara IRA. It was widely believed that Fr Griffin’s killers used a local civilian to collaborate, as Micheál Ó Droighneáin recalled: “I know definitely that he [Fr Griffin] had decided to refuse to leave his home at the behest of British forces and more especially of any stranger. Therefore, my opinion is that the individual who called him was known to him.” Volunteer Joseph Togher recalled: “it was an inside job concocted and carried out by the local company of Auxies stationed at Lenaboy”:

We were convinced that the caller (a tout for the Auxiliaries) was none other than William Joyce … I intercepted a letter from Joyce to an Auxie, which, after being broken down, revealed that Joyce had the RIC cipher that was in use that particular month. Michael Staines, our liaison officer, confronted Divisioner Cruise of the RIC with this information, as Cruise had continually denied Joyce’s association with the RIC. Had we had this information earlier, Joyce would have been executed.

It is highly likely that Fr Griffin was killed by members of D Company of the Auxiliaries in the belief that he had information on the disappearance of Patrick W. Joyce, the national school teacher killed by the East Connemara IRA, the previous week. The police probably assumed that Fr Griffin, being a supporter of the Volunteers, may even have delivered the final rites to Joyce. Alternatively, the Auxiliaries may have targeted Fr Griffin’s fellow priest Fr O’Meehan, who was also associated with the Volunteers, and kidnapped Fr Griffin in his absence. It is probable that Fr Griffin was lured to his death by William Joyce, accompanied by two RIC or Auxiliaries, probably on the pretence of a sick call, by whom he was transferred to a car through Salthill and subsequently to Lenaboy Barracks. Unlike in the killing of the Loughnane brothers during the same month, Fr Griffin’s body showed no obvious signs of torture, and the military inquest concluded he was killed “four of five days” prior to the recovery of his body.

Shortly after Fr Griffin’s disappearance, William Joyce, who was believed to have lured him to his death, joined the 4th Worcester Regiment and departed with them to England. He subsequently achieved infamy as the Nazi propagandist, Lord Haw Haw, and was hanged at Wandsworth Prison in January 1946. The body of national school teacher Patrick Joyce was not recovered until 1998 when a farmer digging on commonage land discovered a wooden box containing a body. The makeshift coffin was exhumed and the Garda Technical Bureau were drafted in to try and establish the identity of the remains. A number of items, including a watch, a stick of chalk and clothing, indicated that the remains were indeed those of Patrick Joyce. (Irish Independent, 8 July 1998)

Further Reading

William Henry, Blood for Blood: The Black and Tan War in Galway (Mercier Press, 2001).

Conor McNamara, War & Revolution in the West of Ireland: Galway 1913–22 (Irish Academic Press, 2018).

Conor McNamara, The Loughnane Brothers, Beagh and Terror in Galway, 1920–21 (Galway County Council, 2020).

Conor McNamara, The Independence Struggle in County Galway, 1918–21, A Research Guide (Galway County Council, 2021).

Timothy McMahon (ed.), Pádraig Ó Fathaigh’s War of Independence (Cork University Press, 2000).

Cormac Ó Comhraí & K.H. O’Malley (eds), The Men Will Talk to Me, Galway Interviews by Ernie O’Malley (Mercier Press, 2015).

Cormac Ó Comhraí, Sa Bhearna Bhaoil: Gaillimh 1913–1923 (Cló Iar-Chonnacht, 2016).

No Comments

Add a comment about this page